Mica, feldspar and kaolin gave Avery and Mitchell Counties world-class status in the early 1900s. The McKinney Mine near Little Switzerland was once the largest feldspar mine in the world, according to the Little Switzerland Business Association.

Feldspar, ground up, has been used as a hardening component in glass-making, a bonding agent in ceramics and an abrasive in household cleaners made by Bon Ami, which owned a mine adjacent to McKinney.

The rugged terrain that became the center of production had been the property of small landowners, one of whom, S.D. McKinney, leased property to Carolina Minerals Company in 1922, Robert Schabilion documents in “Down the Crabtree.”

Decades of mica mining left behind piles of flung-away feldspar, which had not been as commercially coveted in the late 19th century. But in 1910, these scrap heaps had brought a shine to the eyes of a gem prospector from Baltimore named William Dibbell. He scrubbed them real nice and sent a shipment to a big ceramic plant in Ohio called Golding Sons. The plant bosses liked the ceramic-grade feldspar so much, they drafted a contract for him to supply Golding Sons with more and more. This allowed Dibbell to found the Carolina Minerals Company of Penland. By 1917, North Carolina was the nation’s top feldspar producer.

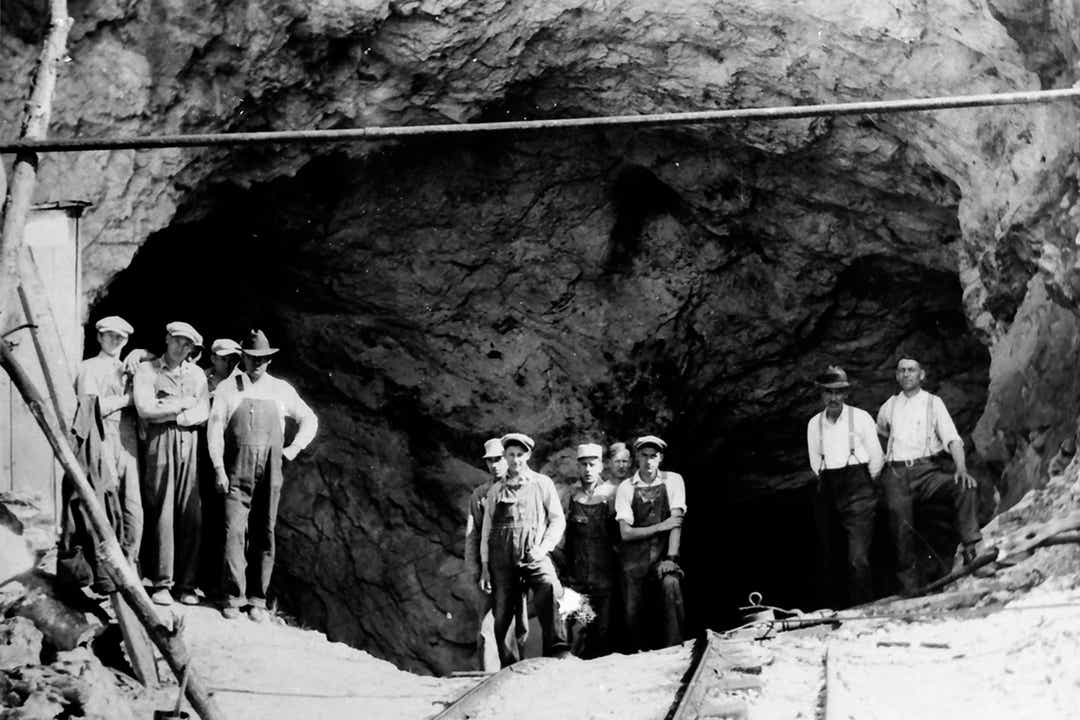

In time, mining companies dug tunnels descending 300 feet, creating caverns called stopes. The quality of the “spar” decreased and the danger of mining increased, Lowell Presnell writes in “Mines, Miners and Minerals,” and the McKinney mine ceased operation in the 1950s.

Feldspar miners

African-Americans had been providing hard labor for the booming mineral industry in the Spruce Pine area when, in 1923, John Goss, an escaped convict, was tagged with the alleged rape of a 75-year-old white woman.

Mob hysteria led to the eviction of all African-Americans from their shanty towns. Business leaders and N.C. Gov. Cameron Morrison had to intervene.

In 1923, Spruce Pine shared with the rest of the nation outbreaks of hysteria over the entrance of African-Americans into the general work force as well as changing attitudes about civil rights following World War I.

Goss had escaped that year from a prison road crew in Spruce Pine at the time that the old white woman had reported having been raped. As in Chicago in 1919, when the drowning of a young black man at a white swimming pool had resulted in a huge riot; and in Tulsa in 1921, when a black man’s contact with a white woman on an elevator had led to military retribution, the Goss accusation elicited a violent response.

On Sept. 26, 1923, 200 white citizens led by a sheriff’s deputy marched to the feldspar miners shanty town and began the forcible eviction of every African-American citizen from the area. Gov. Morrison, a “Red Shirts” white supremacist leader who opposed African-American citizenship, but who also opposed lynching, called the National Guard into Spruce Pine to enable the return of African-Americans.

J.E. Burleson, a prominent Mitchell County citizen, wrote Morrison, urging the state to prosecute the men who had made the racial attack, which he warned “is going to keep men from investing in the mines.”

Unprotected by due process laws, Goss was captured in Hickory, brought back to Spruce Pine under guard, and tried and sentenced in under two hours. The men of the mob who evicted the African- American community ended up paying a small fine for misdemeanor rioting.

The feldspar industry became even more important with the boom in the construction of highways, sewer lines, and water lines. African-American labor was essential and families migrated to work sites.

Executives of the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railroad, which had been extended to Spruce Pine in 1912, felt they had to enlarge the depot there to prevent the mixing of races in the waiting room. When P.H. O’Brien, whose construction company was building roads in Spruce Pine, had been confronted by the armed deportation mob, he had begged them, he said, “to please let our labor alone,” saying his men were “law abiding Negroes that I brought from Alabama.”

In November 1923 at a special court session in Bakersville, Goss was convicted of rape. He strongly professed his innocence before and after the trial, but finally confessed just before his execution, the Dec. 9, 1923, issue of the Asheville Citizen reported.

“The scene attending the electrocution of the negro was not unlike the 50 or so others that have taken place ... about 70 persons witnessed the electrocution, including several negroes.”

Black workers had been essential to hard labor jobs in the region which often drew from prisons. Goss had been at the end of a 15-year term and had, according to the reports, escaped camp. His conviction for criminal assault had rested solely on the woman’s testimony. The other feldspar miners, under the protection of state troops, returned to their work.

In the consideration of how African-Americans might be better represented in monuments, one might nominate the Mitchell County feldspar miners.

Rob Neufeld writes the weekly “Visiting Our Past” column for the Citizen-Times. He is the author of books on history and literature, and manages the WNC book and heritage website, “The Read on WNC,” at thereadonwnc.ning.com. Contact him at RNeufeld@charter.net or 505-1973; @wnc_chronicler.

https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/2019/08/04/visiting-our-past-feldspar-mining-and-racial-tensions/1876796001/

2019-08-04 11:00:00Z

CBMidWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3LmNpdGl6ZW4tdGltZXMuY29tL3N0b3J5L25ld3MvMjAxOS8wOC8wNC92aXNpdGluZy1vdXItcGFzdC1mZWxkc3Bhci1taW5pbmctYW5kLXJhY2lhbC10ZW5zaW9ucy8xODc2Nzk2MDAxL9IBLGh0dHBzOi8vYW1wLmNpdGl6ZW4tdGltZXMuY29tL2FtcC8xODc2Nzk2MDAx

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Visiting Our Past: Feldspar mining and racial tensions - Asheville Citizen-Times"

Post a Comment