Fishing for salmon at Brooks River, Katmai National Park and Preserve/Barbara Moritsch

Katmai National Park And Preserve Vs. The Pebble Mine

“The basis for conservation has to be love…There are lots of different approaches to conservation, but I don’t think any of them will work unless there’s a personal connection between the individual and the natural world.” --Michael Soule interview, The Sun magazine, April, 2018.

By Barbara Moritsch

A recent trip to Katmai National Park and Preserve in Alaska inspired me to dive more deeply into this idea. Does love of a certain place in nature develop only if one has a personal connection with that place, one that comes from direct experience? Must we visit a place before we are driven to protect it?

With its vast green boreal forests, lakes, rivers, salmon, and brown bears, Katmai had been on my bucket list forever. I’d hoped to work there during my National Park Service career, but life took a different turn. I finally got there in early August 2019. My brother, Marc, and I flew to King Salmon, and then were shuttled to park headquarters and the floatplane dock. I stepped inside the building and noticed a table offering crafts and beadwork for sale. Items included stacks of bumper stickers and a rack of beaded earrings, each displaying a red circle with a slash across the words “Pebble Mine.” I’d heard of the proposed mine, but didn’t know exactly where it was and didn’t understand its significance. That changed over the next four days.

The pilot of an old de Havilland Beaver float plane waved us down the dock and loaded us in a hurry; the cloud layer was dropping. A 25-minute flight took us to Katmai’s Brooks Camp, near the mouth of the Brooks River on Naknek Lake. Katmai became a national monument in 1918 to preserve the site of a cataclysmic 1912 volcanic eruption at the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Additionally, the region is home to about 2,200 brown bears, and monument boundaries expanded over time to protect the bears and their habitat. In 1980, Katmai was designated a national park and preserve. Brown bear protection has become a major role for the park.

The NPS operates a visitor center, ranger station, campground, and auditorium at Brooks Camp. Additional services, including meals and lodging, are provided by Brooks Lodge. Accommodations include 16 small cabins, each with two sets of bunk beds. Think rustic. The lodge is popular. Reservations a year in advance are advisable, or one can enter a lottery 18 months in advance. The camp operates from early June to mid-September.

…All About the Bears, 'Bout the Bears

Upon arrival, we left our luggage at Cabin 23 and walked to the ranger station for a mandatory bear safety talk. The message was simple. The bears lived here; we were visitors. Bears always had the right-of-way. We were to stay at least 50 yards away at all times. But, this was not always possible. Bears do not comprehend 50 yards.

Marc and I had lunch (buffet-style, and, yes, salmon is part of almost every meal) and then hiked 1.2 miles to the Brooks Falls bear-viewing platforms. The start of the trail crosses a new bridge and elevated boardwalks spanning the Brooks River, built to replace an old floating bridge. Benefits include better visitor access and less disturbance to wildlife. Huge, heavy gates at each end of boardwalks and bridges keep the bears out to prevent humans and bears from coming face-to-face.

Once across the bridge, the trail follows a dirt road for a bit, then changes to a narrow path. Dense stands of spruce and a variety of shrubs flank the trail, including the flashy magenta fireweed. Visibility off-trail is very poor, and bears can be anywhere. One visitor likened it to a scene from The Wizard of Oz. One morning on the walk back to camp we spotted a huddle of visitors ahead. They signaled to us to stop because there was a bear near the trail. The bear was just leaving, but this group had been trapped for an hour between two bears, one of whom decided to nap in the middle of the trail. Because bears rule, the visitors had to wait until the nap was over.

A new bridge helps visitors both view, and stay away, from the bears drawn to the salmon run in the Brooks River/NPS

Two raised platforms provide views of Brooks Falls. The upper one brings you closest to the action—a visual and auditory feast. The constant watery refrain of the falls. Fish too numerous to count driven by instinct to leap over the six-foot-high falls to spawn upriver. Bears large and small laser-focused on catching salmon, aiming to win the annual fattest bear contest. Optimistic gulls waiting for fish scraps to float their way. A scene both dramatic and serene that has played itself out for thousands of years.

The bears have favorite fishing spots and techniques. Older, more experienced bears get the select locations, lounging in deep pools below the falls where fish congregate, or standing at the fall’s upper lip to wait for a 4,500-calorie morsel to jump into waiting jaws. A few of the upper lip bears ate only the fattiest parts of the fish, the brains and eggs, and let the remains float downriver. Younger bears feed on those remains, and practice pouncing on fish in shallows downriver. At one point, we saw 19 bears around the falls.

Katmai’s bears depend on Katmai’s fish. At least 36 species occur in park waters, including all five species of Pacific salmon found in North America: coho, chinook, sockeye, chum, and pink. The bears’ staple food is sockeye. The largest sockeye run in the world occurs annually in this region beginning in late June. Tens of thousands of fish can enter the Brooks River from Bristol Bay in days or even hours. By the end of July, a million fish may have moved from the bay into the Naknek system of lakes and rivers.

Normally, the migration through the Brooks River stops at the end of July. Most bears leave the area, then return in September in search of dead and dying salmon. But things were different in 2019.

A salmon run in the Brooks River/Barbara Moritsch

June and July of 2019 were the warmest months ever recorded in Anchorage. Air temperatures at Brooks Camp reached about 90˚F in early July, which led to higher than normal water temperatures. Heat stress killed salmon in many areas, while some fish returned to the ocean or delayed their swim upriver until temperatures cooled. When we visited in early August, thousands of salmon were still migrating through the Brooks Falls area.

On our last morning in Katmai, I rose early and walked to the lake shore to photograph the sunrise. No one was around. All was quiet. I stood on the sand and stared through a lens to capture silver gray and gold ripples on the water.

After the shutter clicked for the fourth time I heard a splash to my right. A bear’s head, then its body, emerged from the water about 20 feet away. I froze, then stepped back very slowly. Lake water sluiced off the bear’s dark brown coat, and the morning sun lit up the flaxen tips of her ears (I’m pretty sure this was a sub-adult female we’d seen the day before). She walked about 15 feet inland amidst beach gravel and driftwood, scraped out a shallow depression with her front paws, and dropped down for a nap.

Within ten minutes, park rangers appeared with portable barricades to close the beach until the nap was over. But those few private golden sunrise moments with the emergent bear were mine forever.

Sunrise over Naknek Lake/Barbara Moritsch

Katmai is home to more than bears and fish. Forty-two mammal species have been documented, including moose, caribou, red fox, wolf, lynx, wolverine, river otter, mink, marten, weasel, porcupine, snowshoe hare, red squirrel, and beaver. Steller’s sea lions, sea otters, harbor seals, northern fur seals, and harbor porpoises occur along the coast. Beluga whales, humpback whales, orcas, and gray whales sometimes use the waters just beyond park boundaries.

Katmai is rich in bird diversity as well. At least 175 bird species have been documented; almost 100 species are waterfowl and shorebirds. I found it odd to learn that no reptiles, and only one species of amphibian, the wood frog, have been reported in Katmai.

And at this point in history, all of this incredible wild diversity—pristine lakes, rivers, wetlands, forests, salmon, bears, birds, everything in Katmai and the entire Bristol Bay watershed face a huge risk of irreversible, catastrophic damage from a proposed mine called Pebble.

A Terrible Idea That Refuses To Die

In 1987, about 40 miles north of Katmai, and almost adjacent to Lake Clark National Park and Preserve, color anomalies in the land surface visible from aircraft caught a mining company’s attention. Exploration holes, coupled with soil samples and geophysical surveys, revealed a massive porphyry copper deposit. Exploration continued until 1997 in the area now known as Pebble West.

In 2001, Vancouver, B.C.-based Northern Dynasty Minerals optioned the property and continued exploration. They discovered another deeper deposit in 2005—Pebble East. As of 2017, data indicated the region held more than 57 billion pounds of copper, 71 million ounces of gold, 3.4 billion pounds of molybdenum, and 345 million ounces of silver.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, if fully mined, the Pebble deposit could produce more than 11 billion metric tons (1 metric ton = approximately 2,200 pounds) of ore, which would make it the largest mine of its type in North America. The deposits are low-grade, meaning they contain relatively small amounts of metals relative to the amount of ore. Mining will be economic only if conducted over a large area, and a large amount of waste material will be produced as a result of mining and processing.

The proposed mine site is a broad, flat valley that divides the Koktuli River and Upper Talarik Creek drainages. The Koktuli flows west from low mountains west of Iliamna Lake and feeds into the Wild and Scenic Mulchatna River. Water from the Koktuli eventually makes its way to Bristol Bay. Water from Upper Talerik Creek flows into Iliamna Lake, then flows southwest to Bristol Bay. Iliamna Lake is Alaska’s largest (about 75 miles long, 22 miles wide, with a surface area approximately 1,000 square miles), and is home to a rare population of freshwater harbor seals. The lake is 15 miles south and downstream of the proposed mine.

Bristol Bay, the recipient of all the fresh water flowing through the proposed mine site, supports the largest sockeye salmon fishery on Earth and the most valuable single salmon fishery in Alaska. It provides approximately 40 percent of the world’s salmon, 14,000 jobs, and $1.5 billion in annual profits. More than 62 million sockeye returned to Bristol Bay in the summer of 2018, the largest recorded run for the bay.

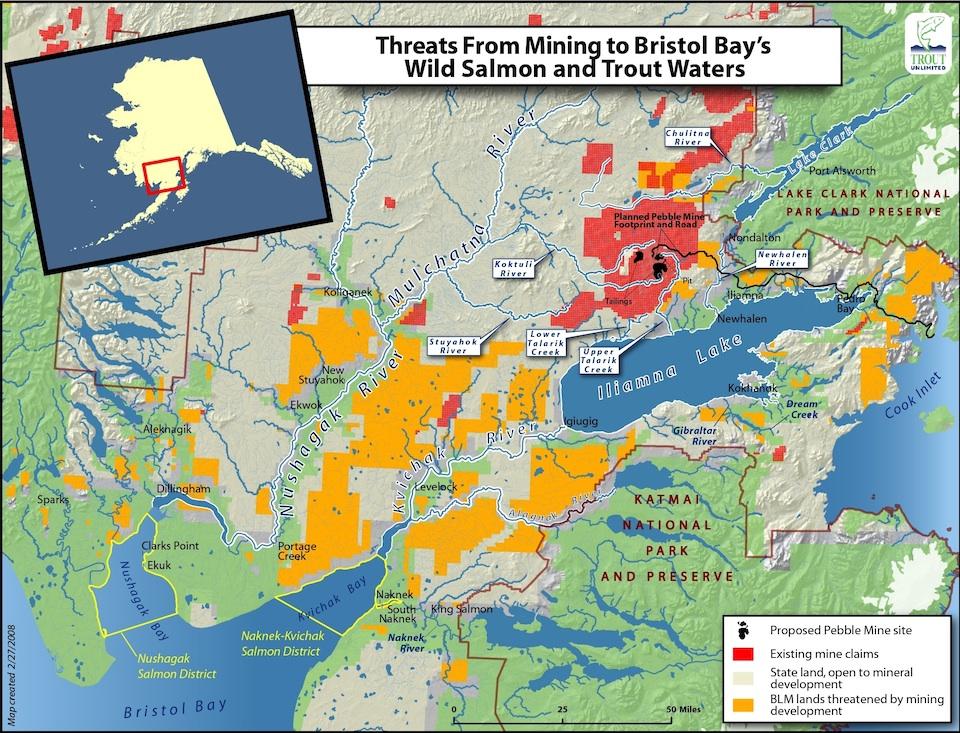

This map shows the proximity of the proposed Pebble Mine and other possible mining could have Bristol Bay and Katmai and Lake Clark national parks/Trout Unlimited

The two federal agencies responsible for permitting and environmental impact assessments for Pebble are the EPA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (ACOE). In 2011, the EPA initiated a three-year assessment of potential impacts of large-scale mining on Bristol Bay’s ecological resources. On July 18, 2014, the EPA issued a press release stating, “The science is clear that mining the Pebble deposit would cause irreversible damage to one of the world’s last intact salmon ecosystems.”

It’s important to note the EPA actually underestimated potential impacts of the mine by not considering the catastrophic damage that would result from a tailings dam failure or pipeline rupture.

Based on the assessment, the EPA issued a Clean Water Act Section 404(c) Proposed Determination that would, if finalized, restrict the discharge of dredged or fill material in the Bristol Bay watershed. The limitations would have stopped the mine project. The mine’s proponent, Pebble Limited Partnership (PLP)—an arm of Northern Dynasty Minerals—promptly sued the EPA.

In mid-May, 2017, a settlement agreement was reached between the Trump administration’s EPA and PLP. The EPA agreed to start a process to withdraw the Proposed Determination, and PLP was allowed to apply for a federal permit. EPA then solicited public comments on withdrawing the Proposed Determination. Of the million responses received, 99.9 percent supported retaining the proposed restrictions. In February 2018, EPA decided to leave the Proposed Determination in place until they had more information on the potential mine’s impacts.

In late February, 2019, the ACOE released a 1,400+-page Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Pebble Project. The mine would extract 1.4 billion tons of ore. It would have an initial 20-year lifespan with a minimum 6,500-foot long, 5,000-foot wide, 1,750-foot deep mine pit. Additional components include an 83-mile long transportation corridor with more than 200 stream crossings and eight bridges; year-round ice-breaking ferry service across Iliamna Lake with two terminals; a port site in Amakdedori Bay (critical habitat for endangered beluga whales); a 270 megawatt power plant; and a 188-mile natural gas pipeline (94 miles of which crosses Cook Inlet).

The entire mine site is currently undeveloped, and not served by any transportation or utility infrastructure. If approved the fully developed mine site (approximately 8,086 acres) would include the open pit, bulk and pyritic tailings storage facilities, overburden stockpiles, material sites, main and open pit water management ponds, seepage collection ponds, sediment ponds, milling and processing facilities, and supporting infrastructure such as the power plant, water treatment plants, camp facilities, and storage facilities.

There would be two tailings storage facilities (essentially large dammed areas)—one about 2,800 acres for bulk tailings, and the second over 1,000 acres for pyritic tailings. The pyritic storage facility also would be used to store potentially acid-generating waste rock during operations. At closure, the pyritic tailings and waste rock would be relocated to the bottom of the completed open mine pit, and maintained in a subaqueous condition in perpetuity by the lake that would naturally form in the pit. Note the site of the Pebble deposit is very active seismically.

The proposed mine would destroy at least 3,500 acres of wetlands and more than 81 miles of streams; disturb wildlife; cause air, water, and noise pollution; impair commercial and recreational fisheries; and permanently alter the rural lifestyles of local communities.

But that’s just the initial phase of Pebble. Even more frightening than what is described above is the DEIS’s discussion of PRFFAs: Potential Reasonably Foreseeable Future Actions. The project proposed in the DEIS is much smaller than the original plan for Pebble, and it’s clear the PLP intends to expand the mine pit significantly and continue mining the prospect for at least 78 years. At that time, milling will continue for 20-40 more years to process low grade ore. PLP plans to mine Pebble for 118 years, yet the DEIS is for a 20-year project.

Some of the wetlands in the Bristol Bay area/EPA

Additionally, more than 1,000 square miles of state land around the Pebble project have been staked with mining claims since 2003. If Pebble Mine development provides infrastructure, the entire surrounding area could become a huge mining district. This first phase of the Pebble Mine is the tip of a massive mining and development iceberg.

The DEIS went out for review and comments on March 1, 2019, with a 90-day review period that was extended for an additional 30 days. More than 685,000 people weighed in to oppose the mine. Organized opposition comes from a broad coalition of commercial fishing interests, local Native tribes, tourism and sport-fishing operators and organizations, and a suite of environmental groups including Trout Unlimited, Natural Resources Defense Council, National Parks Conservation Association, National Wildlife Federation, and Sierra Club, among others.

Comments to the DEIS are available on the ACOE’s website. The response from various federal agencies is particularly telling. The Department of the Interior, EPA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Marine Fisheries Service all said, in varying language, that the DEIS was grossly inadequate, lacked important information, underestimated potential impacts of the project, and failed to address cumulative impacts. Comments from numerous Bristol Bay organizations raised similar concerns.

U.S. Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Oregon), Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), and Sen. Dan Sullivan (R-Alaska) all expressed concerns about the DEIS, stating the document had gaps and deficiencies, and, in DeFazio’s words, was “fundamentally flawed.”

Critical questions surround the PLP’s financial viability. Since 2011, four of the world’s largest mining companies have backed out of the project. Alaska Public Media reported on December 5, 2019, that Northern Dynasty Minerals (which owns 100 percent of the PLP) lost about $40 million in the first nine months of 2019. The company’s deficit now exceeds $400 million. Numerous requests for information about the PLP’s financial status have gone unanswered.

On July 30, 2019, in a sudden move that blatantly denied science in favor of politics, the EPA withdrew the Proposed Determination that would have stopped the Pebble Mine. According to CNN, EPA staff were told about the withdrawal one day after Alaska’s governor Mike Dunleavy met with President Trump on Air Force One in Anchorage, a full month before the news went public. Apparently, top EPA officials were shocked by the announcement—they’d planned to oppose the project.

The ACOE expects to publish a Final EIS by June of 2020, and then issue a Record of Decision on Pebble’s 404(c) permit soon after. The short timeline for this EIS process is unprecedented for a project of this size and complexity. The ACOE published its Notice of Intent to prepare the EIS in March 2018, and plans to complete the process by Fall 2020. If the permit is issued, PLP could begin digging in the headwaters of Bristol Bay in the next 3-5 years, and if this “streamlined” permitting process happens, the CEO of PLP, Tom Collier, will receive a $13 million personal bonus.

On October 9, 2019, more than a dozen groups sued the EPA over its reversal of the 2014 Proposed Determination. Trout Unlimited filed a separate lawsuit on the same day, and Bristol Bay groups filed a related lawsuit on October 8th.

Protecting The Wild Places

In light of the proposed Pebble Mine, I return to my earlier question: Must we visit a place to be driven to protect it? If the answer is “yes,” Katmai and nearby Lake Clark National Park and Preserve (each with over four million acres) may not get the support and protection they need and deserve from the general public who may not ever visit these parks.

From 2008 to 2017, the number of visitor use days reported in Katmai fluctuated between 25,000 and 30,000 per year. Between 1923 and 2018, the park received approximately 1,655,782 visitors. Lake Clark averages about 23,000 visitors per year. Compare these numbers to Yosemite’s almost five million visitors per year. Imagine if a foreign corporation proposed to develop a huge mine that could destroy the headwaters of Yosemite’s Merced River—it would be a complete non-starter.

There are many reasons to stop Pebble. It’s not just about the commercial fishery. It’s not just about Native American subsistence. It’s not just about tourism, sportfishing, or hunting. It’s about all these things, but it’s also about leaving wild places wild. It’s about acknowledging that some places are too special to destroy with development. It’s about giving the salmon and the bears and the kittiwakes, the moose and the otters and the mergansers, the gray wolves and the lynxes and the caribous and all the other beings who call this area home a chance to survive and thrive. It’s about saying enough is enough, the ecological costs of the Pebble Mine project are simply too great. It’s about saying “No.” It’s about love.

Go to Katmai or Lake Clark if you can. Fall in love. And if you can’t visit, trust those who have, trust that these lands must be protected at all costs. The Pebble Mine must be a non-starter.

Brown bear waiting for fish on Brooks River/Barbara Moritsch

https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2020/01/katmai-national-park-and-preserve-vs-pebble-mine

2020-01-19 08:01:47Z

CBMiXmh0dHBzOi8vd3d3Lm5hdGlvbmFscGFya3N0cmF2ZWxlci5vcmcvMjAyMC8wMS9rYXRtYWktbmF0aW9uYWwtcGFyay1hbmQtcHJlc2VydmUtdnMtcGViYmxlLW1pbmXSAQA

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Katmai National Park And Preserve Vs. The Pebble Mine - National Parks Traveler"

Post a Comment